Staff notation reveals certain kinds of musical structures at a glance, because they form recognizable shapes on the staff. The convention of writing the key signature at the beginning of the piece makes it easier to see those underlying structures as it relates to chords, melodies, and to patterns of distances between notes. Those changes translate into different patterns of lines and spaces which you can recognize by their shapes.

Staff notation reveals certain kinds of musical structures at a glance, because they form recognizable shapes on the staff. The convention of writing the key signature at the beginning of the piece makes it easier to see those underlying structures as it relates to chords, melodies, and to patterns of distances between notes. Those changes translate into different patterns of lines and spaces which you can recognize by their shapes.

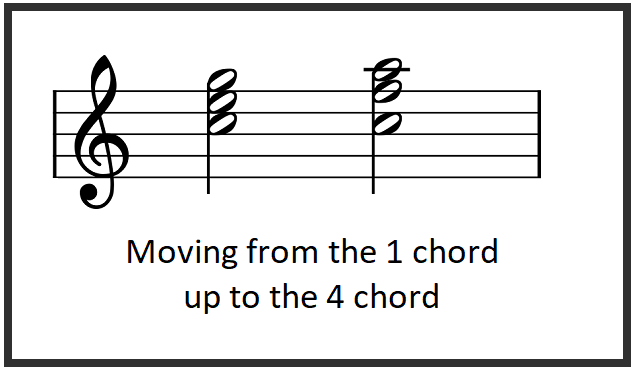

Let’s start with a chord triad in root inversion (low to high: 1, 3, 5). A root inversion triad is either three consecutive lines, or three consecutive spaces. For instance, the example below is what it looks like when you use voice-leading to go from a root inversion 1 chord up to the 4 chord (C major up to F major). The low note stays the same, and the other two notes each go up by one scale degree.

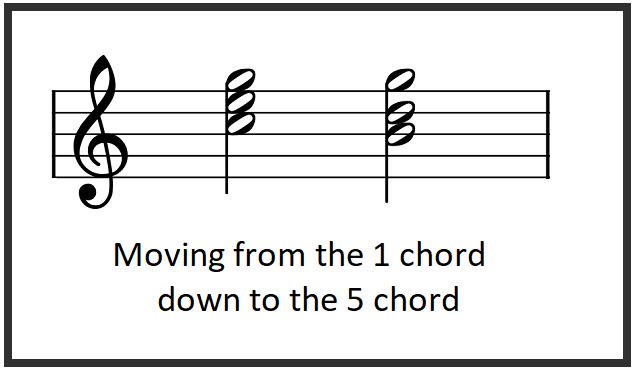

The example below uses voice leading to go from a 1 chord in root inversion down to 5 (C major down to G major). The high note stays the same, and the other two notes each go down by one scale degree.

There are several particulars you have to keep track of. For one thing, the chords can be either major or minor, depending on the key. The examples above both start with a 1 chord triad written in spaces. There’s a different set of patterns when the 1 chord triad is written on lines, but the distance relationships are exactly the same. This is only one example of how you can learn to systematically “chunk” reading music.

Staff notation can be a bridge to your destination, or a barrier between you and your goals. Some people say staff notation is a fatally-flawed system. But apart from Hau notation, no one seems to have come up with any easier way to read music. (Tablature for guitar is a special case.)

Reading Staff Notation – Part 1

© 2019, 2020 Greg Varhaug